Purbabanga-Gitika

Purbabanga-Gitika a collection of folk ballads of East Bengal. These ballads, composed orally and performed among the rural communities, are important resources of bangla literature.

The ballads were collected from Mymensingh, Netrakona, Chittagong, Noakhali, Faridpur, Sylhet and Tripura. The main collectors of these ballads include chandra kumar de, dinesh chandra sen, ashutosh chaudhuri, jasimuddin, Nagendrachandra Dey, Rajanikanta Bhadra, Bihari Lal Roy and Bijay Narayan Acharya.

Over 50 ballads are included in the collection, among them Dhopar Pat, Maisal Bandhu, Kanchan Mala, Kamala Ranir Gan, Madankumar O Madhumala, Nejam Dakater Pala, Dewan Isha Khan, Manjur Ma, Kaphenchora, Bheluya, Hatikheda, Aynabibi, Kamal Sadagar, Chawdhurir Ladai, Gopini-Kirtan, Suja-Tanayar Bilap, Baratirther Gan, Nurunnechha O Kabarer Katha and Paribanur Hanhala.

Most of these ballads were composed in the 14th century, with some being composed in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The composers of these ballads were uneducated or half-educated farmers or boatmen. Their themes included love affairs, rivalry between different zamindars, and significant events effecting the life of the people. These were composed in the form of rhymes or panchali. Later, groups of singers used to set them to music and perform them in villages.

Chandrakumar De started publishing some of these folk ballads from 1913. These attracted the attention of Dineshchandra Sen who met Chandrakumar. With his help Dineshchandra collected quite a few of these ballads from the villagers. Calcutta University provided financial support for the collection which was published as Purbabanga-Gitika in 1926. Dineshchandra translated these ballads into English. The collection, titled Eastern Bengal Ballads, was published in four volumes by Calcutta University in 1923.

Volume 1: Eastern Bengal Ballads : Mymensigh ((1923), contains ten ballads:

Mahua (1-30pp), Malua (31-80), Chandravati (81-102), Kamala (103-138), Dewan Bhavna (139-162), Kenaram the Robber Chief (163-180), Rupavati (181-204), Knaka and lila (205-242), Kajal Rekha (243-282), and Dewan Madina (283-312=.

Sen in the first volume presented baromashi songs or the songs of twelve months. In these songs each of the twelve months of the year presents, as it were, a bioscopic scene of the landscape of Bengal.

The earliest poetic tradition of the country was that bengali poem could not be complete withoutbaromasi or an account of the twelve month. We have found baromasi even from the days of aphorisms of Dak and Khana in the ninth century (Dinesh Chandra Sen).

Kamalar Baromasi

Kamalar Baromasi collected by Poet Jasim Uddin in Faridpur, Bangladesh about thirty years ago. The song represents songs of separation with the happy end (Dr. Dusan Zbavitel, The Development of baromasi, Folklore of Bangladesh, Bangla Academy,1987):

are solid.

Paddy of different colours ripened in my fields

I shall prepare rice from paddy of various colours

The merchant of my heart is not at home, to whom

shall I give it?

In this month of Paush, there is the darkness of

Paush.

nights being dark, thieves go from one house to

another.

let the thieves come, I am not afraid of them.

Father and brother are the ring round my body and

my father-in-law, the merchent.

In this month of Magh, coldness is like poison

Kamal lays the bed with cotton mat in the inner

house.

Laying in the bed with the cotton mat she looks at the

room-

Why does the room of the poor woman look empty?

The cotten robe, the cotton mat, the cotton pillow on

her breast.

You sinful cotton pillow, there is no answer in thy

mouth!

In this month of Phalgun, householders sow the seed.

The girl a cup full of poison.

I shall eat poison, i shall eat venom, I shall die,

But shall never (again) marry a boatman.

The boatman is the great scoundrel, a servent of the

business.

Having married me, he went away and never cared

about me.

In this month of chaitra, the wind chaitali is at its

height.

The wife whose merchant at home is very proud

What a wife is she whose merchant is not at home?

I am unhappy wife, I am dying in pains.

In this month of Baisakh, there is spinach and jute

leaves.

All people eat spinach, the limbs of the wife are

bitter.

She cooked and prepared spinach and poured it on a

plate.

My dear merchant is not at home, whom shall I give it?

In this month of Jaysto hot is the sun

Hundred of mangoes are ripe and huge jack-fruits

I would eat mangoes, I would eat jack-fruits,

milk of five cows.

If my dear merchent were at home, we would play

together.

In this month of Ashar, there is new water in Ganges,

The milkwoman shouts :"Take curds! Take Curd!

Whose curds who will take, who would like to eat it?

The merchant is not at home, my days pass in fasting.

In this month of Sraban, householder cut the paddy

the kora-bird calls, sitting on the rice stalk.

Dakcalls, damphala calls, bora calls, sitting there,

the call of the cruelkokil made my ribs split.

In this month of Bhadra tal-fruits (palm) are ripe in the trees,

The young girl went out with a plate in her hands.

She took her plate, she took a box, she took a quilt on

her head

Wandering around she went where her dear merchant

had gone.

In this month of Ashwin there is the new

Durga festival.

Let the brahmin wives offer flowers (to the goddess)

Let them offer offer flowers, let them take the offerings

home.

If my dear mervhant comes home, I shall offer to

him.

In this month of Kartik , betel-buds are on the

trees.

The dear merchant comes home, with an umbrella

over his shoulder.

* In a leap year, Caitra has 31 days and Caitra 1 coincides with March 21.

The history of calendars in India is a remarkably complex subject owing to the continuity of Indian civilization and to the diversity of cultural influences. Early allusions to a lunisolar calendar with intercalated months are found in the hymns from the Rig Veda, dating from the second millennium B.C.E. Literature from 1300 B.C.E. to C.E. 300, provides information of a more specific nature.

Before the introduction of the Bangla Calendar, agricultural and land taxes were collected according to the Islamic Hijri calendar. However, as the Hijri Calendar is a lunar calendar, the agricultural year did not always coincide with the fiscal year. Therefore, farmers were hard-pressed to pay taxes out of season. In order to streamline tax collection, the Mughal Emperor Akbar ordered a reform of the calendar. Accordingly, Amir Fatehullah Shirazi, a renowned scholar of the time and the royal astronomer, formulated a new calendar based on the lunar Hijri and solar Hindu calendars. The resulting Bangla calendar was introduced following the harvesting season when the peasantry would be in a relatively sound financial position. In keeping with the harvesting season, this new calendar initially came to be known as the Harvest Calendar, or Fôsholi Shôn. The new "Fôsholi Shôn" was introduced on 10 March / 11 March 1584, but was dated from Akbar's accession to the throne in 1556. The new year subsequently became known as Bônggabdo or Bangla Shôn ("Bengali year").

The zero year of the Bangla calendar coincides with the zero of the Islamic Hijri calendar since it was introduced by a Muslim Mongol conqueror of India, Emperor Akbar, descendant of Babar, Tamerlane and Chenghis Khan. Today the two calendars have diverged and have two different years.

The Bangla calendar was made a solar calendar to better coincide with harvest times and facilitate better collection of taxes. This caused the difference between the Hijri year and the Bangla year. The Hijri lunar calendar is 11/12 days shorter than the solar year and so has raced ahead. The Hijri year today (January, 2003) is 1422 while the Bangla year is 1409.

The Bengali Calendar in use today was created by Emperor Akbar (or rather someone under him) on March 10 or 11th 1584/5 AD. It amalgamated the old Indian calendar and the Islamic Hijri (Arabic) calendar and was originally called Tarikh-e-Elahi... now Bangla Shaal (possibly the name of the old calendar). That was not, however, year zero. Since Akbar had ascended the throne in the year 1556 AD and his new calendar was backdated to that year which was the year 963 in the lunar Hijri era (Islamic calendar). So the new Bangla calendar began at 963 with zero coinciding with the zero of the Hijri calendar.

The months, Boishakh, Joishtho, Asharh, Srabon, Bhadra, Ashwin, Kartik, Agrahayon, Poush, Magh, Falgun, Chaitra are used. Boishakh, Joishtho, etc. are Bengali names as opposed to non-Indian names used by Akbar. The Bangla names from the older calendar prevailed. Originally in the region, the first of Chaitra was the beginning of the new year but a new date was selected by Akbar and his administration. It was a date selected from both the Arabic and the Bengali calendars. In 963 AH (Hijri) the first arabic month, Muhurram, had coincided with Baishakh (Boishakh). So the first of Boishakh (Pahela Boishakh) was selected as the first day of the year replacing Chaitra first. Even though the names of the original

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Translated by: ZBAVITEL Dušan - ceský indolog

D.-k.: L'orientalisme en Tchécoslovaquie (též angl., nem. a rus.), Praha 1959; (s E. Heroldem a K. Zvelebilem), Indie zblízka, Praha 1960 (nem. 1961); Rabíndranáth Thákur. Vývoj básníka, Praha 1961; Ocenka Tagorom Dviženija svadeši posle 1905, Moskva 1961; Bengali Folk-Ballads and the Problem of their Authenticity, Calcutta 1963; (s J. Markem), Dvakrát Pákistán, Praha 1964 (nem. 1966, rus. 1966); (s kol.), Bozi, bráhmani, lidé. Ctyri tisíciletí hinduismu, Praha 1964 (rus. 1969); The Rise of Modern Literature in Asia, with Special Reference to Bengal, Calcutta 1966; Lehrbuch des Bengalischen, Heidelberg 1970, 3. vyd. 1997; Non-Finite Verbal Forms in Bengali, Praha 1970; (s kol.), Moudrost a umení starých Indu, Praha 1971; Bangladéš. Stát, který se musel zrodit, Praha 1973; Bengali Literature, Wiesbaden 1976; (s kol.), Setkání a promeny, Praha 1976 (pol., 1983); Jedno horké indické léto, Praha 1982 (rus. 1986); Staroveká Indie, Praha 1985; (s kol.), Bohové s lotosovýma ocima, Praha 1987 (2. vyd., 1997); Divadlo južnej Azie, Bratislava 1987; Sanskrt, Brno 1987; (s D. Kalvodovou), Pod praporem krále nebes. Divadlo v Indii, Praha 1988; Hinduismus a jeho cesty k dokonalosti, DharmaGaia, Praha 1993; (s J. Vackem), Pruvodce dejinami staroindické literatury, Trebíc 1996; Otazníky staroveké Indie, Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, Praha 1997.

Note: I am very grateful to the Bengali Academy Dacca, for having been given an oppertunity to consult their collection, and to my friend, the Poet Jasim uddin, dacca, who placed to my disposal some baromasiscollected by him. - Dr. Dusan Zbavitel,Oriental Institut Praha, czechoslavakia.

Poet Jasim Uddin collected more than 10 thousands folk songs. During his life time Bangla Academy refused to publish the collection with interpretation and for this ground he refused to accept the Bangla Academy literary Award in 1975. It took seven years to publish Jari Gan by the Bangla Academy. It is pity that academy did not show any intrest. It is a great national loss that the academy did not take any action to preserve our national heritage.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

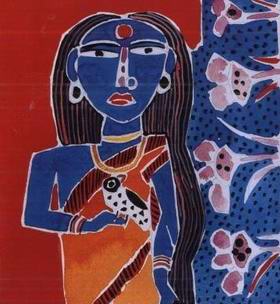

Chandraboti

Chandraboti was a sixteenth-century poet from Mymensingh who has been immortalized as the heroine of Joy-Chandraboti, a Mymensingh Geetika. The ballad tells the story of Chandraboti’s love for Joychandra. The two were to get married when Joychandra rejected her for a Muslim girl. Joychandra tried to return to Chandraboti, but Chandraboti rejected her former lover, who committed suicide by drowning himself. Chandraboti’s father suggested that she occupy herself by translating the Ramayana from Sanskrit to Bangla. Chandraboti started the work but died before she could complete it. Dinesh Chandra Sen included Chandraboti’s Ramayana in Purbabanga-Gitika. The following is a transcreation by Nuzhat Amin Mannan of poet Nayan Chand Ghosh’s Chandraboti.